Meet Emil Majuk, Project Manager of the Shtetl Routes at the Grodzka Gate - NN Theatre

"Properly conducted tourism of Jewish heritage carries with it great potential for civic education and counteracting xenophobia."

What is the Grodzka Gate?

The "Grodzka Gate - NN Theatre" Centre is a cultural municipal institution in Lublin, Poland dedicated to researching and recovering historic memory and local cultural heritage, particularly that of the Jews in Lublin and its surroundings. Our institution is situated at the Grodzka Gate (in Polish - Brama Grodzka), which is a medieval city gate. In the early 1990s, the Gate became home to a group of young artists called the NN Theatre. At that time they knew nothing about the city's Jewish past. They were not aware that the enormous empty space on one side of the Gate led what was once the Jewish Quarter. Now all that is left is a huge parking area, green space and new roads where there used to be houses, synagogues and streets.

When people from the NN Theatre realized the significance of this emptiness, the core mission of the Center became the remembrance of the Jewish people who lived in Lublin before World War II. We think of our Centre, since 1998 called Osrodek "Brama Grodzka - Teatr NN" ("Grodzka Gate - NN Theatre" Centre) as an "Ark of memory" in which old photographs, documents and memories are constantly being collected. We carry out artistic and educational activities within this symbolic meeting space - a ground for discussing the past and building the future.

What is your role in this institution?

I have been professionally related to Brama Grodzka for 15 years. I work as project manager, mostly in the activities related to a heritage interpretation, a new media storytelling and an international cooperation. My main activity since 2013 is a project called Shtetl Routes: Vestiges of Jewish Cultural Heritage in Cross-border Tourism.

Most of the "Grodzka Gate - NN Theatre" Centre activities are connected to the local heritage of Lublin, especially the Jewish heritage of the Lublin, but the city does not function without links to the region - the Lublin region and in a broader sense to the East Central Europe.

The main aim of Shtetl Routes is to support tourism development based on the Jewish cultural heritage in the borderlands of Poland, Belarus and Ukraine, with particular attention to a cultural phenomenon that was specific to Central and Eastern Europe, and which strongly influenced the local cultural landscape: the shtetl (Yiddish for small town). At the beginning the project was implemented as part of the framework of the Cross-Border Cooperation Programme Poland - Belarus - Ukraine, one of the elements of the European Neighbourhood Partnership Instrument.

Shtetl Routes offers tours (both real and virtual), guidebooks, maps, trainings for tour guides and networking tools for those who are interested in the Jewish history of Central and Eastern Europe as an integral part of shared European heritage. Check out The Shtetl Routes travel package.

In the guidebook "Shtetl Routes. Travels Through the Forgotten Continent" which is one of the elements of the project, we tell the stories of sixty-two towns located in the borderland of Poland, Belarus, and Ukraine and the stories of the Jewish communities inhabiting these towns. Our intention is to evoke the tales of Jewish culture, which used to be so important to the towns of the borderland, by referring to surviving objects of cultural heritage, such as synagogues, prayer houses, cemeteries, schools, cinemas, printing houses, factories and sometimes ordinary houses. This is why the book is full of quotations, references to memories, stories from literature and Yizkor Books. We also show how these towns attempt to draw on their Jewish heritage today, in places where Jews still live and where there are no Jews anymore.

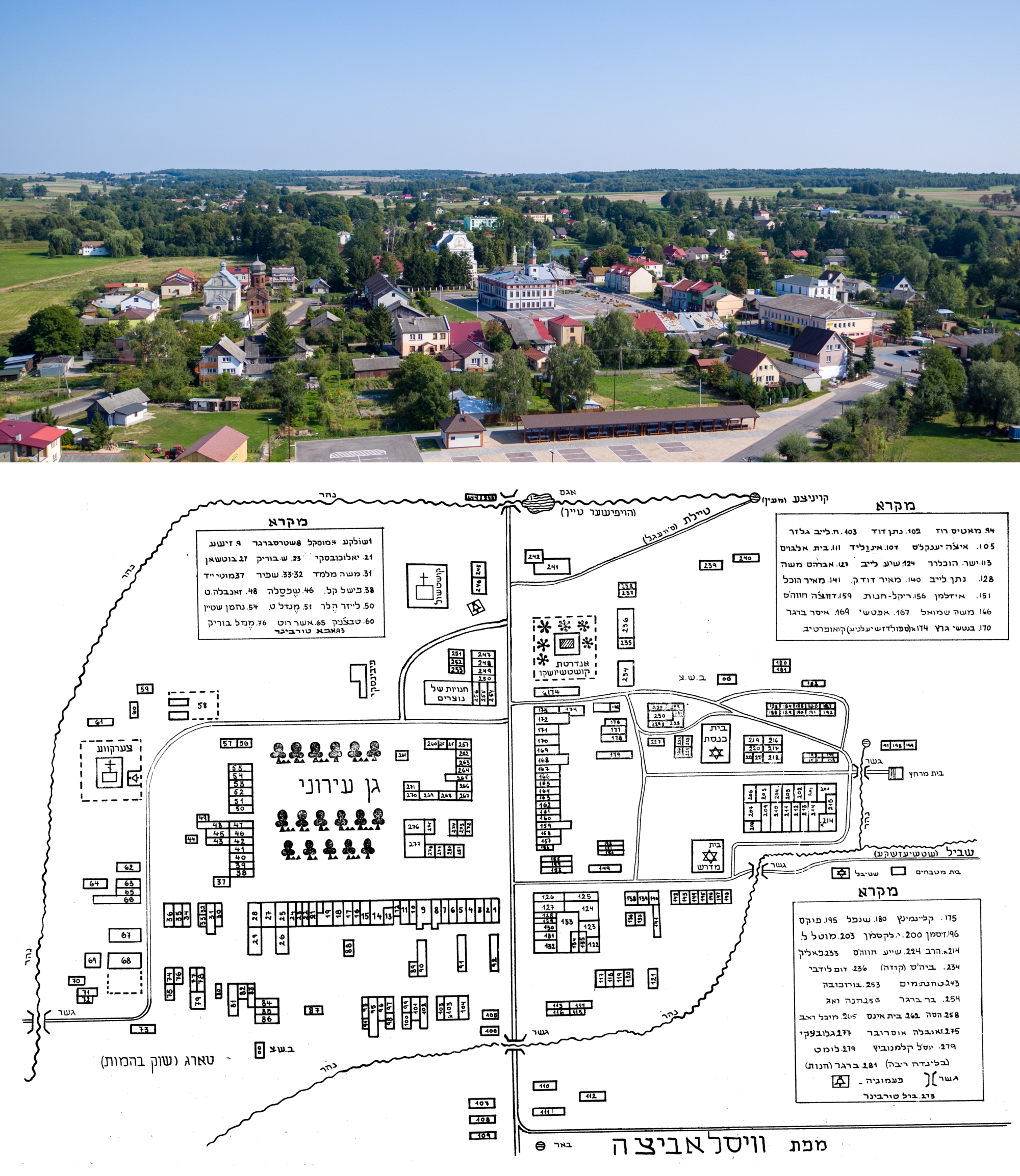

Shtetl Routes is a cultural tourism focused part of the "Grodzka Gate - NN Theatre" Centre's broader programme called the "Forgotten Continent", the aim of which is to tell the story of the former yiddishland, using various artistic and educational tools; for example - see the Atlas of Memory Maps.

What is your personal connection to the story of the shtetls?

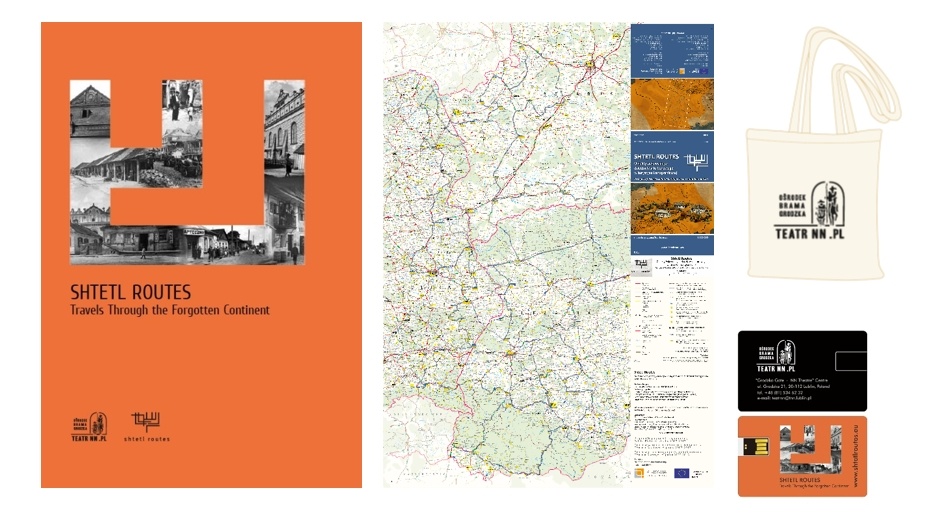

I was born in small town called Wojslawice, which through centuries was a typical multicultural shtetl inhabited by Poles, Ukrainians and Jews. As a result of the Shoah and ethnic cleansings during World War II this town became monoethnic, but its historical multireligious heritage is still visible in the local landscape - i.e., through preserved sacral buildings - the former synagogue and churches - Catholic and Orthodox. Since childhood I heard a lot of stories about local coexistence between Christians and Jews from my grandmother . both peaceful and colourful stories, as well tragic and drastic ones. I always found these stories to be interesting and important. So - when I met the folks from the Brama Grodzka - NN Theatre, with similar feelings and understandings, quite quickly I became part of the team.

Now I'm also involved in the process of creation of the new exhibition for the local museum of Wojslawice located in the former synagogue, where we aim to tell this multithreaded story and give respect to Shoah victims from my home town.

I have spent most of my life in small towns - at the moment I live in another former shtetl - Bychawa, a small town near Lublin, where a XIX century synagogue with beautiful frescos inside still stands. There is a local foundation whose aim is to preserve and revitalise this historical monument; I hope it will succeed.

What is the situation of Polish Jewish heritage with respect to Europe?

Jewish people have lived in Europe for more than two thousand years, so Jewish culture has been an element of European heritage since the beginning. The case of Poland is special for several reasons. The eastern border of the European Union runs through land, which for over four hundred years, from the mid-16th century to the mid-20th century, was the most important centre of Jewish culture in the world. The blooming of this culture began when the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania created a dual state called the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, from which contemporary Poland, Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine came into existence. The events of World War II and the Holocaust destroyed this world, yet Jewish cultural heritage has been permanently imprinted upon the cultural landscape of my part of Europe.

The tourism of Jewish heritage in Central and Eastern Europe, in places affected by the Holocaust, is by its nature ambivalent. It allows travellers to touch on the vast diversity and vitality of Jewish culture, but at the same time it is a journey in the footsteps of genocide, marked by missing mezuzahs and sites of execution of innocent people. Both kinds of experiences - the centuries of life living in cultural diversity as well as the great destruction caused by hatred for the Other, are highly important for the European identity.

The European Union was created as a reaction to the tragedies of World War II, as an attempt to prevent similar events from taking place in the future. Properly conducted tourism of Jewish heritage carries with it great potential for civic education and counteracting xenophobia.

What is the role of the Jewish Heritage in Europe nowadays in your opinion?

The EU's motto is "United in Diversity" and Jewish culture is one of European cultures - a very universal one. Understanding European Jewish story in all its diversity, both flourishing periods and exclusion processes, should help build a better European future for all of us.

Tell us an anecdote: Which activity do you remember most warmly and why?

In the framework of Shtetl Routes we organize trainings for tourist guides and local heritage activists. One was very special - in Autumn 2015 for the most advanced group of participants of our previous trainings we organized a 10 day transborder tour - with quite an amazing mixture of knowledgeable 50 participants from 5 countries (Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, Israel and Germany) on board one bus. During our trip we visited twenty-four places in three countries, crossing the EU and Schengen zone border three times (which is not the easiest and quickest thing to do).

One of the tour participants was Hryhoriy Arshinov, from Ostroh (Ukraine), a town with amazingly rich historical heritage [see video: Ostroh. In the shadow of history] and almost totally ruined synagogue. More less in the same time Sergei Kravtsov from Hebrew University published on Jewish Heritage Europe web-magazine an essay entitled "The Great Maharsha Synagogue in Ostroh: Memory and Oblivion. Have we reached the point of no return?". After our tour and reading of Sergei Kravtsov's essay Hryhoriy understood that he is the only person who could do it - and as a completely grassroots initiative - he started to renovate the synagogue. And he did it - two years ago we had the opportunity to present the NN Theatre performance "Stories from the Gate" in the partly restored synagogue. Last month, the major renovation phase reached its successful conclusion. The marvellous Great Maharsha Synagogue in Ostroh has been saved. Check out the video and story.

When did you start to be part of AEPJ and what has it brought you since then?

We applied for the Routes Incubator in 2018 and became an official member of the AEPJ last year. It gave us a lot of new contacts with people who share similar passions, as well as insightful support from experts from AEPJ's Scientific Board.

What challenges do you have ahead of you for this 2020?

The Covid-19 pandemic has totally destroyed all tourism, so all our plans connected to cultural tourism events had to be cancelled. Given this we will invest more time in digital storytelling, virtual exhibitions and e-learning (see Shtetl Routes - 3d models). I would like to also use this year for strategic planning for future development of Shtetl Routes.